sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Server

Client->>Server: Initial Request

Server->>Client: HTML File

Client->>Server: Subsequent Request

Server->>Client: HTML File

Web Programming

Lecture 6

AJAX, JSON and RESTful APIs

Seoul National University of Science and Technology

Information Technology Management

Lecture slides index

April 8, 2025

Course structure

Agenda

- HTTP

- APIs

- RESTful APIs

- JSON

- AJAX

- fetch

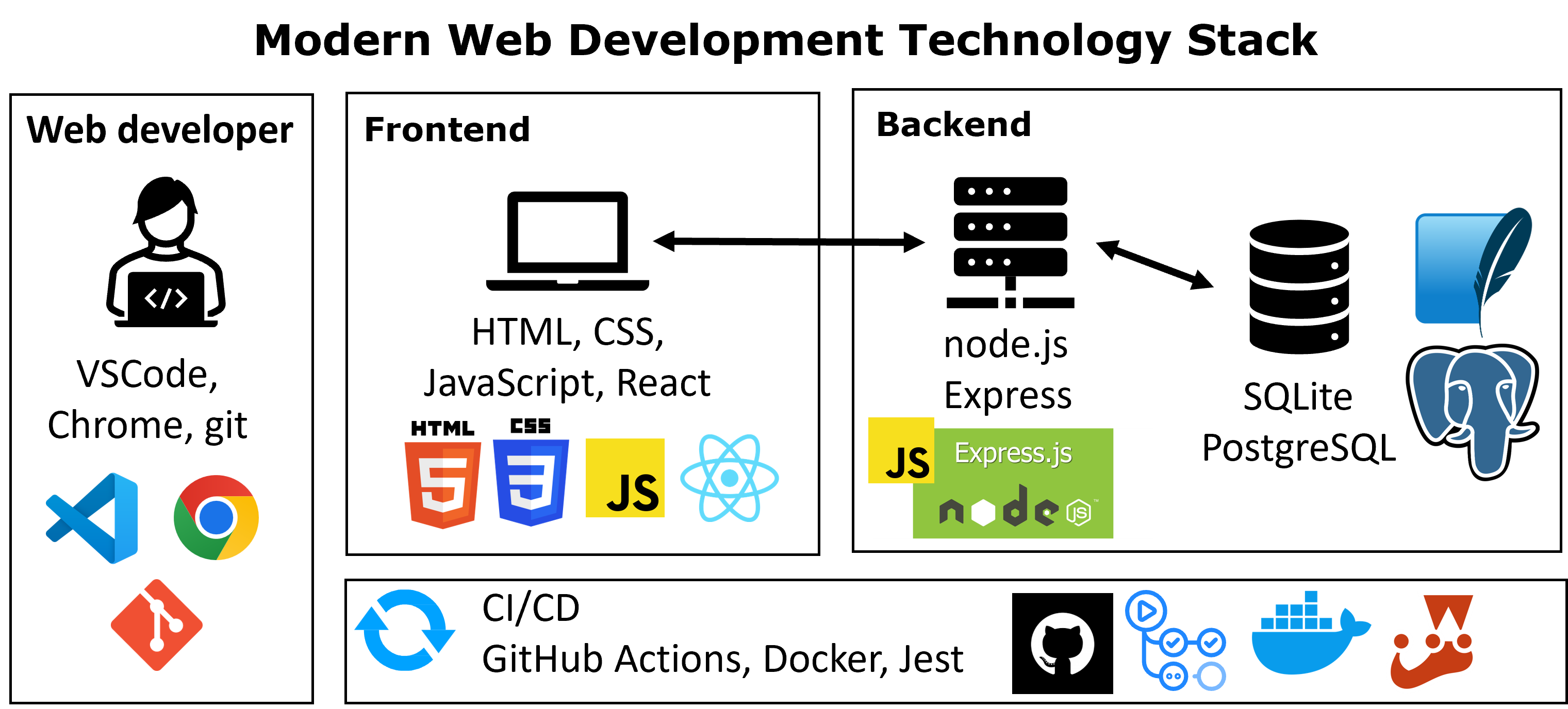

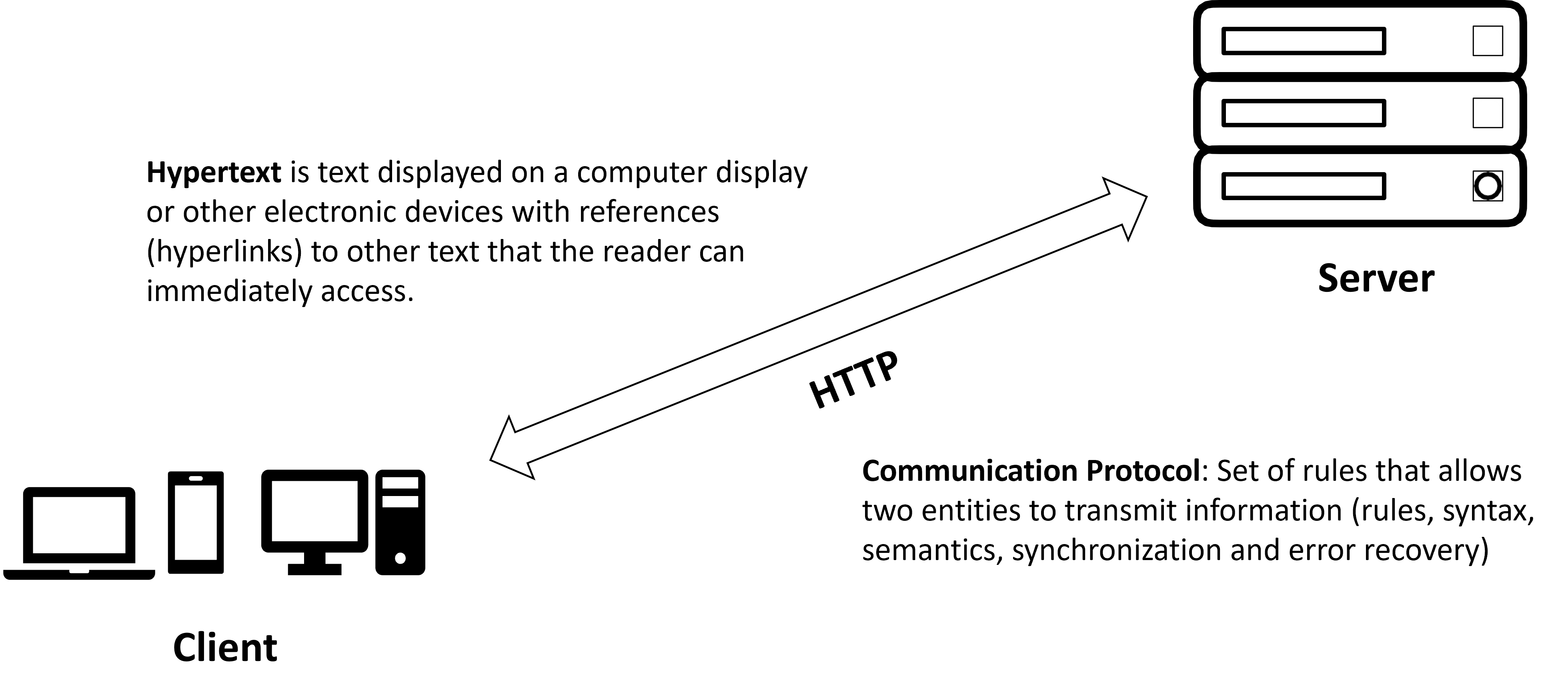

HTTP – server and client relationship

- Although web development can be quite complex, we can simplify it by focusing on how the server and client interact in a typical web application.

Two main participants:

- Server: The machine running the application, handling database queries and other backend tasks.

- Client: The software on the user’s device—usually a browser executing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript—also called the frontend.

They communicate over HTTP: the client issues a request, and the server returns a response, forming the standard request/response cycle.

Request and response

- HTTP revolves around two primary elements: the request and the response.

- The client issues a request to the server, and the server processes it before returning a response.

- Each message is composed of multiple parts, which we will explore in the following slides.

- As shown, a single server can serve many clients at once. This is the standard web application architecture: the server handles incoming requests and delivers the corresponding responses.

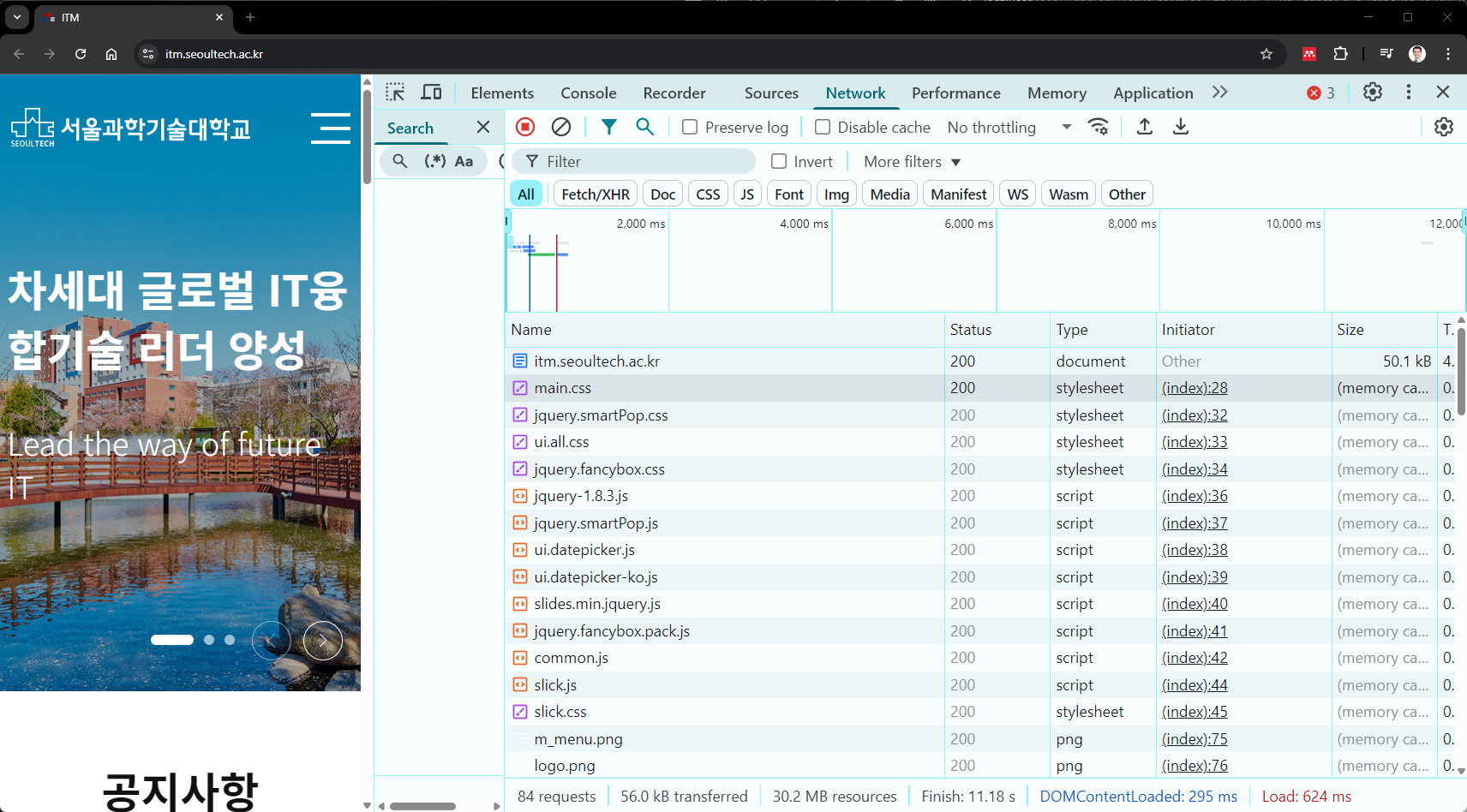

HTTP – Multiple Client Requests to Multiple Servers

- A client often sends multiple HTTP requests to one or more servers.

- Check the following HTTP snippet

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://server1.com/style.css">

</head>

<body>

<img src="https://server3.com/image.png">

<script src="https://server2.com/script.js"></script>

</body>- In this case, requests go to

server1.com,server2.com, andserver3.com. - Each server returns its specific resource.

- Open your browser’s DevTools (Network tab) on a site like https://itm.seoultech.ac.kr to observe all requests and responses.

HTTP request and response to the ITM website

- Pay attentioin at the bottom part you can easily see that this page is sending 84 requeswts targeting different servers to render the page.

- Key resources include: CSS files, favircons, JS files, images, videos and raw data

Server-side rendering (SSR)

- Early web apps were simple and JavaScript usage was limited.

- Pages were rendered on the server, and the client only received HTML, CSS, and JS.

- This approach is called server‑side rendering and is still used today.

Disadvantages:

- Every user interaction requires the server to re-render and resend the page.

- Generates high network traffic.

- Users experience blank screens during refreshes.

- Especially poor on early smartphones (low processing power, slow connections).

The relationship between the server and client in the server-side rendering approach

Client-side Rendering (CSR)

- In client‑side rendering, the server sends the initial HTML, CSS, and JS files to the client.

- JavaScript then takes control and renders the views on the client side.

- The server only sends data, and the client renders the page

- Single‑Page Application (SPA) is the most common pattern today (it is not absolutely required to be CSR)

- Initially complex to implement, but frameworks like Angular, React, and Vue.js have made SPA development popular.

- The SPA pattern still uses HTTP, but via Asynchronous JavaScript and XML (AJAX)requests.

- Backend applications have evolved into APIs that serve data to clients—and even other servers.

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Server

Client->>Server: Initial Request

Server->>Client: HTML File

Client->>Server: AJAX Call

Server->>Client: JSON Payload

The relationship between the server in the AJAX approach

Mastering HTTP

- You may be surprised to learn that HTTP requests and responses are largely human-readable plaintext.

- Currently, the most used version of the protocol is the HTTP/1.1 version, but the HTTP/2 version is gaining popularity

- Let’s take a deeper look at the different parts that compose the request and the response:

- headers

- methods

- payloads

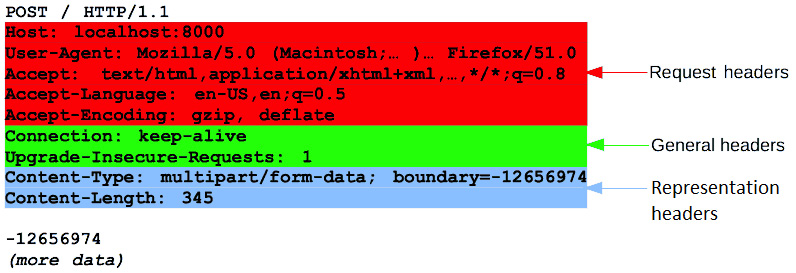

HTTP headers (request)

- Each request and response has a set of headers.

- These are key-value pairs and provide additional information about the request or the response.

- Representation headers

content-type,content-length

- General headers

keep-alive,upgrade-insecure-requests

- Request headers

accept,accept-encoding,accept-language,hostanduser-agent

- We can understand many things about a request, such as the type of content the client is expecting, the language, and the browser used

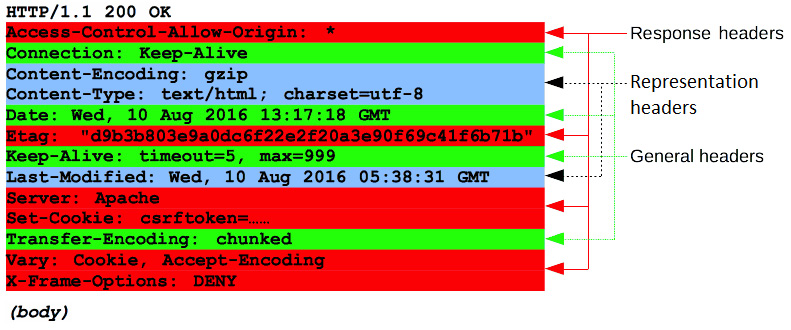

HTTP headers (response)

- Representation headers

content-type,content-encoding,last-modified

- General headers

connection,date,keep-alive,transfer-encoding

- Response-specific headers

access-control-allow-origin,etag,server,set-cookie,vary,x-frame-options

- Provide metadata to help browsers and apps digest and render responses

- Critical for security:

X-Frame-Optionsprevents framing

Feature-Policycan disable camera/microphone, etc.

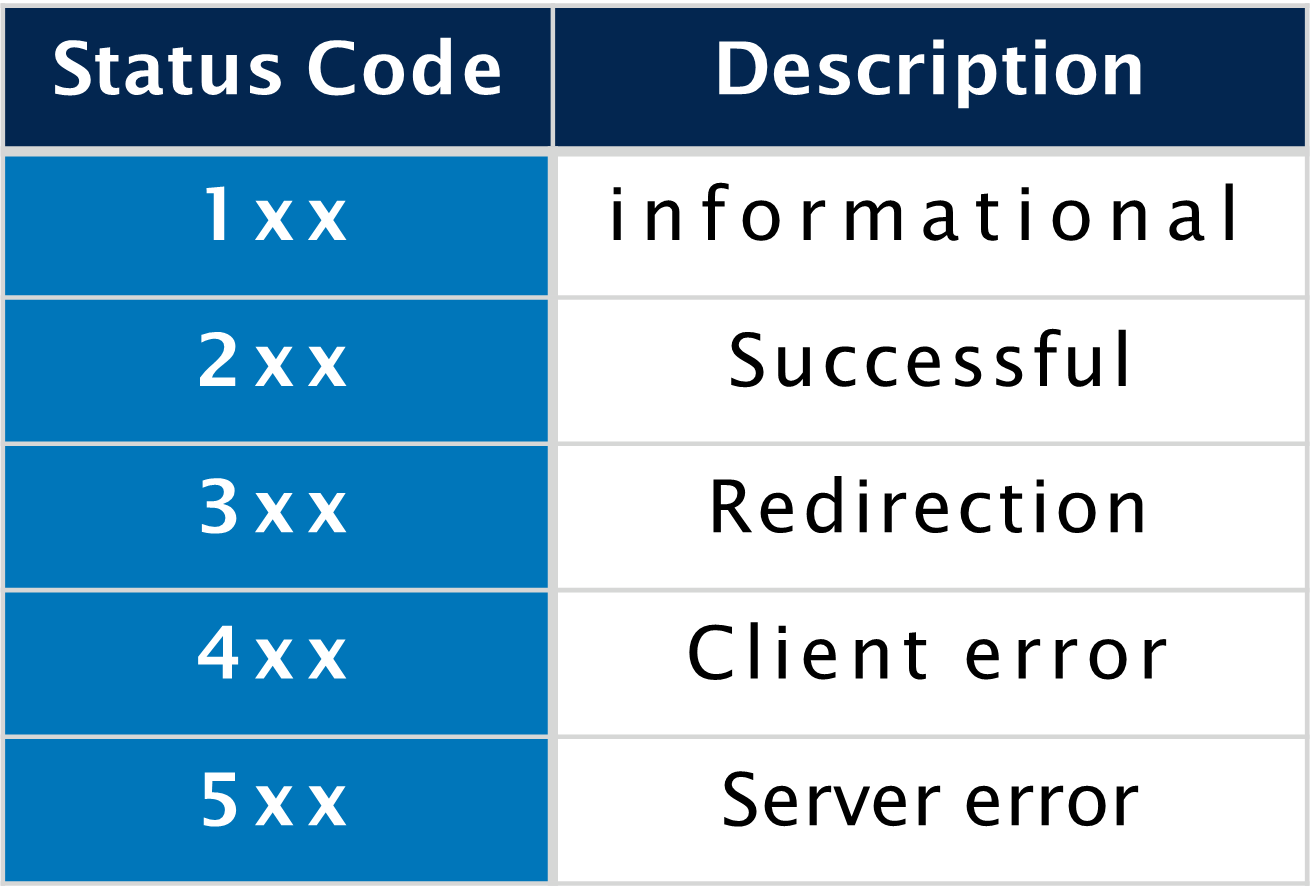

HTTP status codes

- With all responses that a web server sends, there is a response code that allows us to understand whether the request was successful or not and can even provide more detailed feedback.

The most common status codes are:

- 200 OK

- 201 Created–> The request succeeded, and a new resource was created as a result.

- 301 Moved Permanently –> The URL of the requested resource has been changed permanently. The new URL is given in the response.

- 400 Bad Request –> The server cannot or will not process the request due to something that is perceived to be a client error

- 401 Unauthorized –> semantically this response means “unauthenticated”

- 403 Forbidden –> The client does not have access rights to the content; that is, it is unauthorized

- 404 Not Found

- 429 Too Many Requests

- 500 Internal Server Error –> The server has encountered a situation it does not know how to handle.

- 503 Service Unavailable.

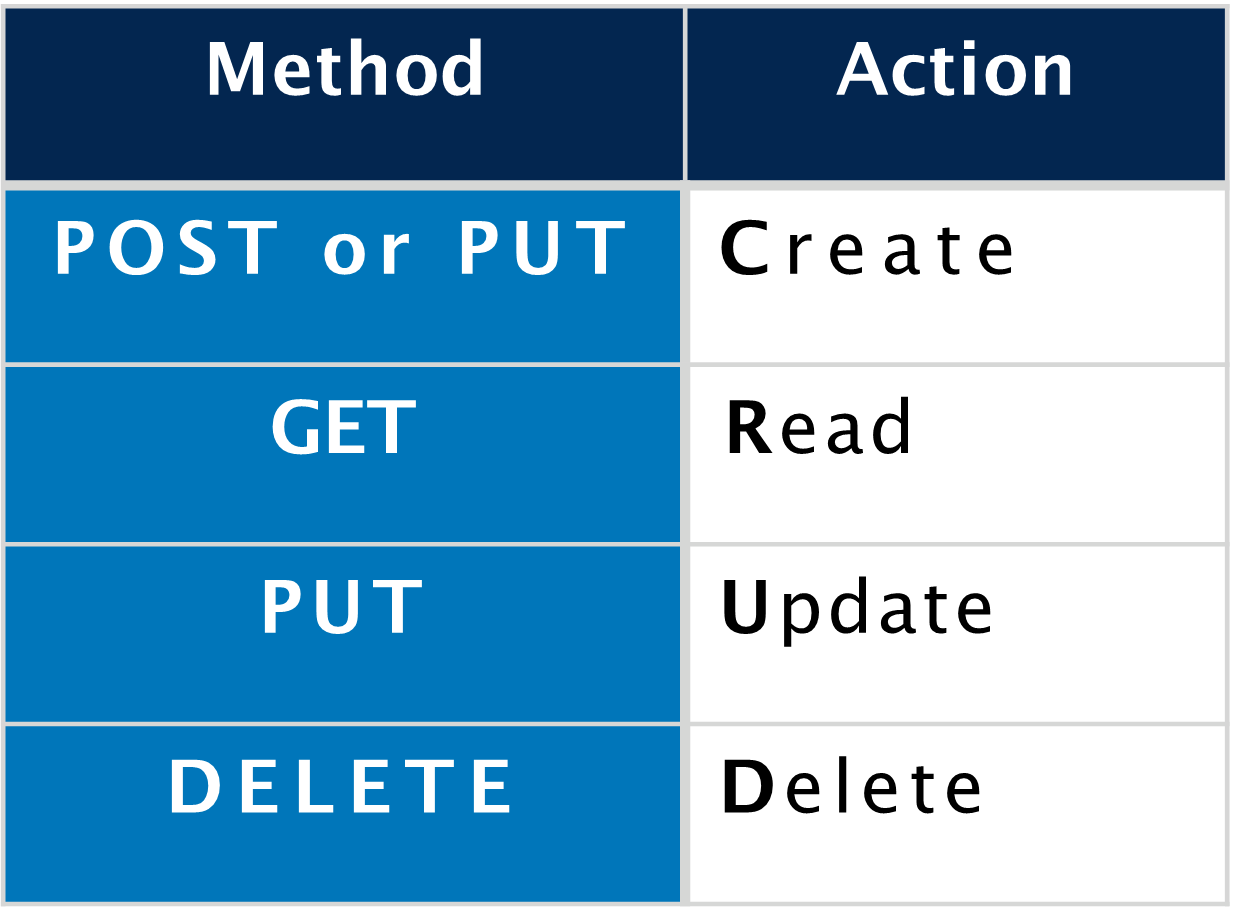

HTTP methods

- HTTP defines a set of request methods to indicate the purpose of the request and what is expected if the request is successful.

- Although they can also be nouns, these request methods are sometimes referred to as HTTP verbs.

- GET: Retrieve a resource (default method used by the browser)

- POST: Create a resource

- PUT: Update a resource

- PATCH: Partially update a resource

- DELETE: Delete a resource

(CRUD) are the four basic operations or actions of persistent storage.

HTTP payloads

- HTTP messages can carry a payload, which means that we can send data to the server, and servers likewise can send data to their clients.

- This is often done with POST requests.

- Payloads can be in many formats, but the most common are the following:

- application/json: Used when sharing JSON data

- application/x-www-form-urlencoded: Used when sending simple texts in ASCII, sending data in the URL

- multipart/form-data: Used when sending binary data (such as files) or non-ASCII texts

- text/plain: Used when sending plain text, such as a log file

Application Program Interface (API)

- An application programming interface (API) is a connection between computers or between computer programs.

- A web API is an API for either a web server or a web browser.

- A client-side web API is a programmatic interface to extend functionality within a web browser or other HTTP client.

- A server-side web API consists of one or more publicly exposed endpoints to a defined request–response message system, typically expressed in JSON or XML by means of an HTTP-based web server.

- APIs come in all shapes and sizes:

- REST (what we’ll focus on)

- SOAP

- RPC/gRPC

- GraphQL

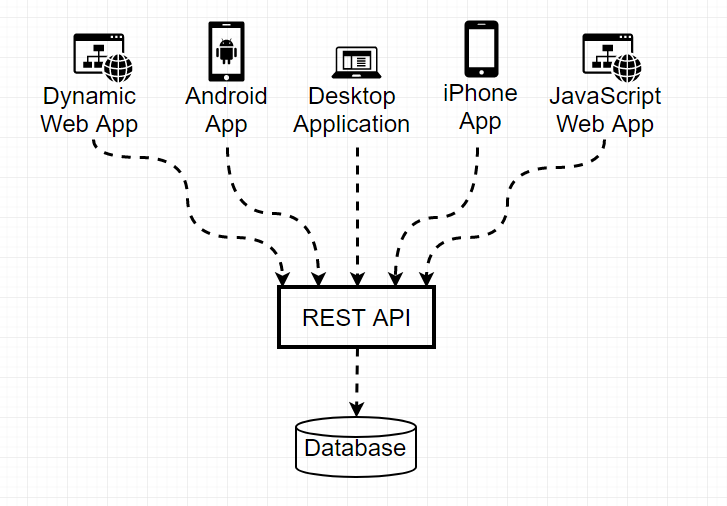

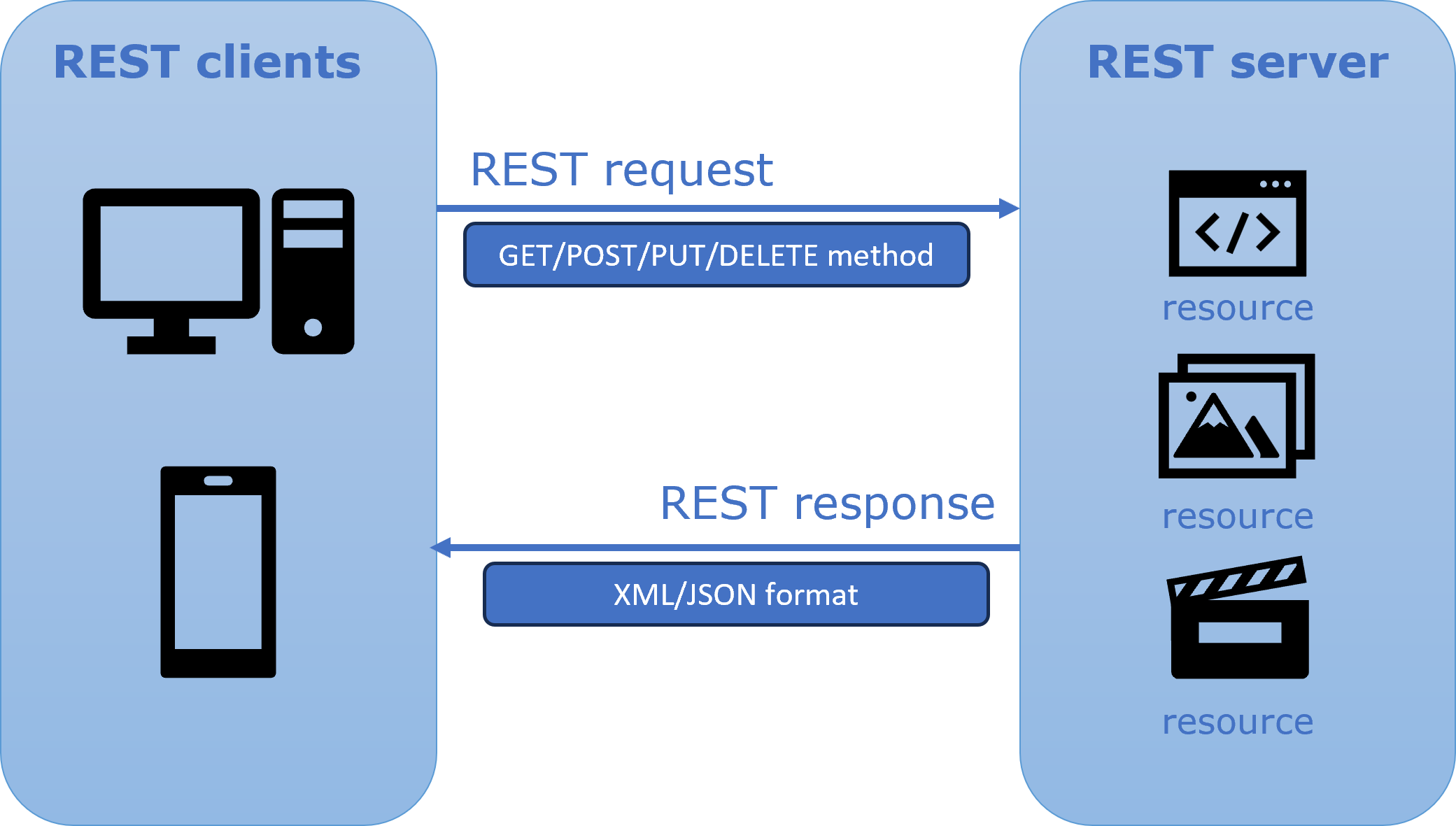

REST APIs

REST stands for Representational State Transfer

Architectural style for designing web APIs

Coined by Roy Fielding in his 2000 PhD dissertation

Resources

- Identified by unique URLs, that denote endpoints

- Accessed and manipulated via HTTP methods

Server Response

- Status code (e.g., 200, 404, 500)

- Payload (JSON, XML, etc.) when applicable

- Status code (e.g., 200, 404, 500)

Example of REST API

- Let’s say that we have a REST API to manage a database of movies.

- We can define the following resources:

- /movies: This resource represents the collection of movies

- /movies/:id: This resource represents a single movie

- The client can perform the following operations on these resources using the aforementioned HTTP methods:

- GET /movies: Get all the movies

- GET /movies/:id: Get a single movie

- POST /movies: Create a new movie

- PUT /movies/:id: Update a movie

- DELETE /movies/:id: Delete a movie

- Most of the time, the server will respond with a JSON payload, but it can also respond with other formats such as XML or HTML.

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)

- Data format that represents data as a set of JavaScript objects

- Natively supported by all modern browsers (and libraries to support it in old ones)

Not yet as popular as XML, but steadily rising due to its simplicity and ease of use- Updated: JSON is a lightweight substitute for XML and it is more popular than XML because of JavaScript’s dominance as the most widely used language of today.

JavaScript objects

let person = {

name: "Philip J. Fry", // string

age: 23, // number

"weight": 172.5, // number

friends: ["Farnsworth", "Hermes", "Zoidberg"], // array

};

person.age;

person["weight"]; // 172.5

person.friends[2]; // "Zoidberg"

let propertyName = "name";

console.log(person[propertyName]); // "Philip J. Fry"- Objects are the most versatile structure in JS

- You can access the fields with dot notation (.fieldName) or bracket notation ([“fieldName”]) syntax

- You can create a new property or overwrite existing ones in an object by assigning a value

Example of JSON

- Keys (attributes) must be in double quotes:

- name: “Fry” → Invalid

- “name”: “Fry” → Valid

- Strings must use double quotes (not single quotes):

- ‘Fry’ → Invalid

- “Fry” → Valid

- No functions, comments, or trailing commas allowed:

- JSON is pure data — not code.

- You can’t include

function(){}or comments like // this is a comment.

JavaScript Objects vs. JSON

- JSON is a way of representing objects, or structured data.

- The technical term is “serializing” which is just a fancy word for turning an object into a savable string of characters

- Browser JSON methods:

JSON.parse( /* JSON string */ )– converts JSON string into Javascript objectJSON.stringify( /* Javascript Object */ )– converts a Javascript object into JSON text

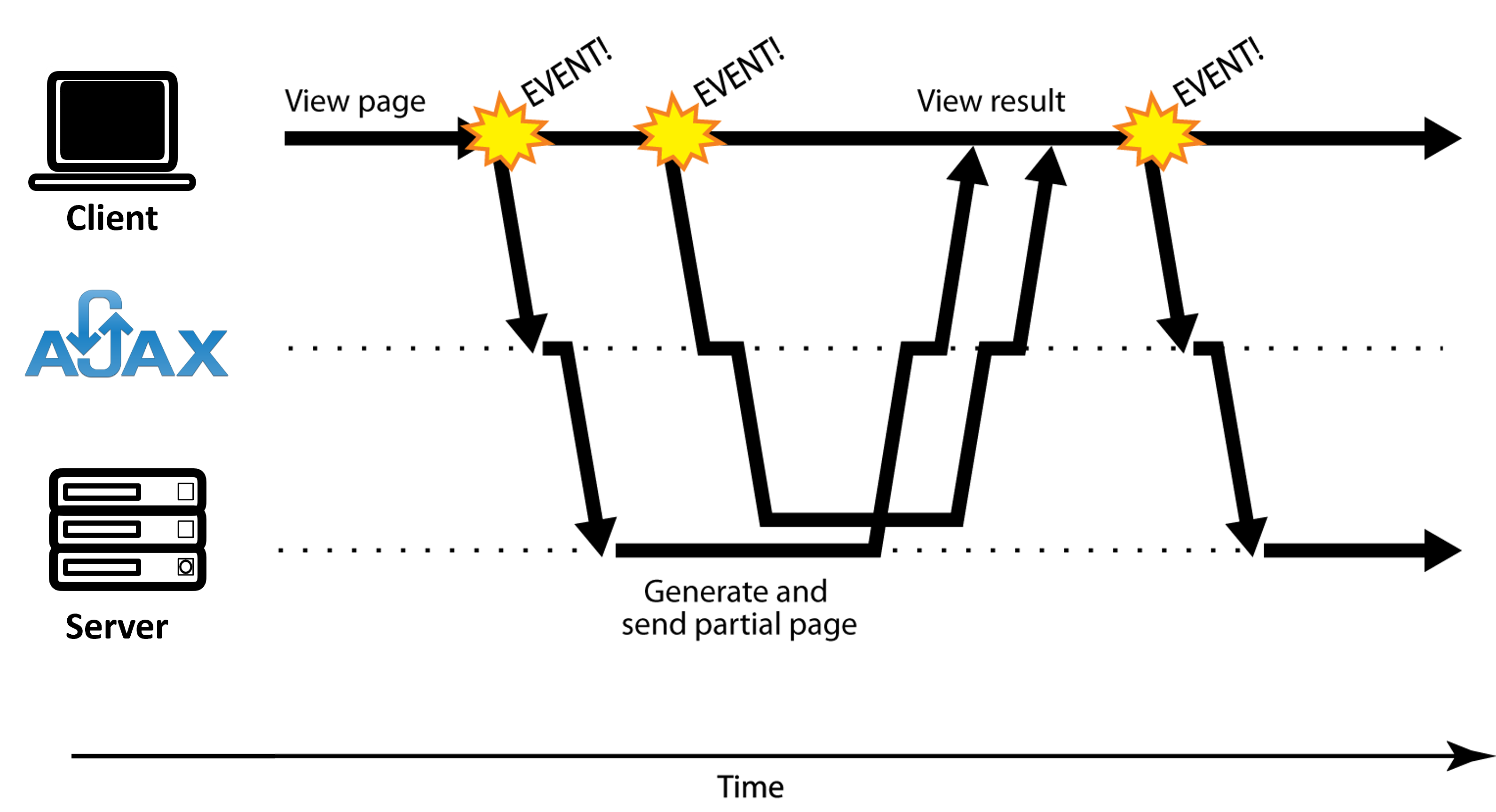

AJAX

- Web application: a dynamic web site that mimics the feel of a desktop app presents a continuous user experience rather than disjoint pages

- Examples: Gmail, Facebook, etc.

- AJAX: Asynchronous JavaScript and XML

- It is not a technology, but rather a programming pattern

- Downloads data from a server in the background

- Allows dynamically updating a page without making the user wait

- Avoids the “click-wait-refresh” pattern

- Currently it should be called “AJAJ”??

AJAX

- XMLHttpRequest(callback-based)

- XMLHttpRequest (XHR) objects are used to interact with servers. You can retrieve data from a URL without having to do a full-page refresh.

- This enables a Web page to update just part of a page without disrupting what the user is doing.

- Fetch API (promise-based)

- It provides a global fetch() method that provides an easy, logical way to fetch resources asynchronously across the network.

- Unlike XMLHttpRequest that is a callback-based API, Fetch is promise-based and provides a better alternative

AJAX with Fetch

- The Fetch API provides a JavaScript interface for making HTTP requests and processing the responses.

fetchtakes a URL string as a parameter to request data (e.g. pokemon information in JSON format) that we can work with in our JS file.

async function populateInfo() {

const URL = "https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/ditto";

await fetch(URL) // returns a Promise!

...

}- We need to do something with the data that comes back from the server.

- But we don’t know how long that will take or if it even will come back correctly!

- The

fetchcall returns aPromiseobject which will help us with this uncertainty.

More on fetch()

- The

fetch()function returns a Promise - When resolved, the value of this Promise is the Response object representing the response from the API

- It contains a lot of information (more than just the pure information we want to get back)

- The information is critical to our implementation

Checking the http status with statusCheck()

- NOT (!!) built into JavaScript (we need to define it)

- But why?? Wouldn’t the promise return by fetch just reject if something fails??

.json() and .text()

- Called on the Response object

- Both of these methods return Promises

.json():- Returns a Promise that resolves to a JavaScript object

- Parsing the contents of the Response object’s body (received as JSON) into an object

.text():- Returns a Promise that resolves to a String

- Parsing the contents of the Response object’s body (received as text) into a String

Generic fetch template

- Here’s the general template you will use for most AJAX code:

const BASE_URL = "some_base_url.com"; // you may have more than one

async function makeRequest() {

let url = BASE_URL + "?query0=value0"; // some requests require parameters

try {

let result = await fetch(url)

await statusCheck(result)

// result = await result.text(); // use this if your data comes in text

// result = await result.json(); // or this if your data comes in JSON

processData(result)

} catch(err) {

handleError(err); // define a user-friendly error-message function

}

}

function processData(responseData) {

// Do something with your responseData! (build DOM, display messages, etc.)

}

async function statusCheck(res) {

if (!res.ok) {

throw new Error(await res.text());

}

return res;

}Next week

Backend development and Introduction to Node.js

Acknowledgements

- Some contents of this lecture are partially adapted from:

- Harvard CS50’s Web Programming with Python and JavaScript, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Materials from University of Washington’s CSE 154 Web Programming (used with permission).

- The Odin Project (main website code under MIT license and curriculum licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- The Fundamentals of Web Application Development (Web Edition) ©2025 Nicholas D. Freeman. All rights reserved. The content is provided for educational purposes only and is not an exhaustive treatment of the subjects.

- freeCodeCamp.org © 2025 freeCodeCamp.org. All rights reserved. The content is provided for educational purposes only and is not an exhaustive treatment of the subjects.

- Node.js for Beginners by Ulises Gascón. Some contents adapted under fair educational use for instructional purposes.

Web Programming