Web Programming

Lecture 5

Asynchronous Programming in JavaScript,

JSON and AJAX

Seoul National University of Science and Technology

Information Technology Management

Lecture slides index

April 3, 2025

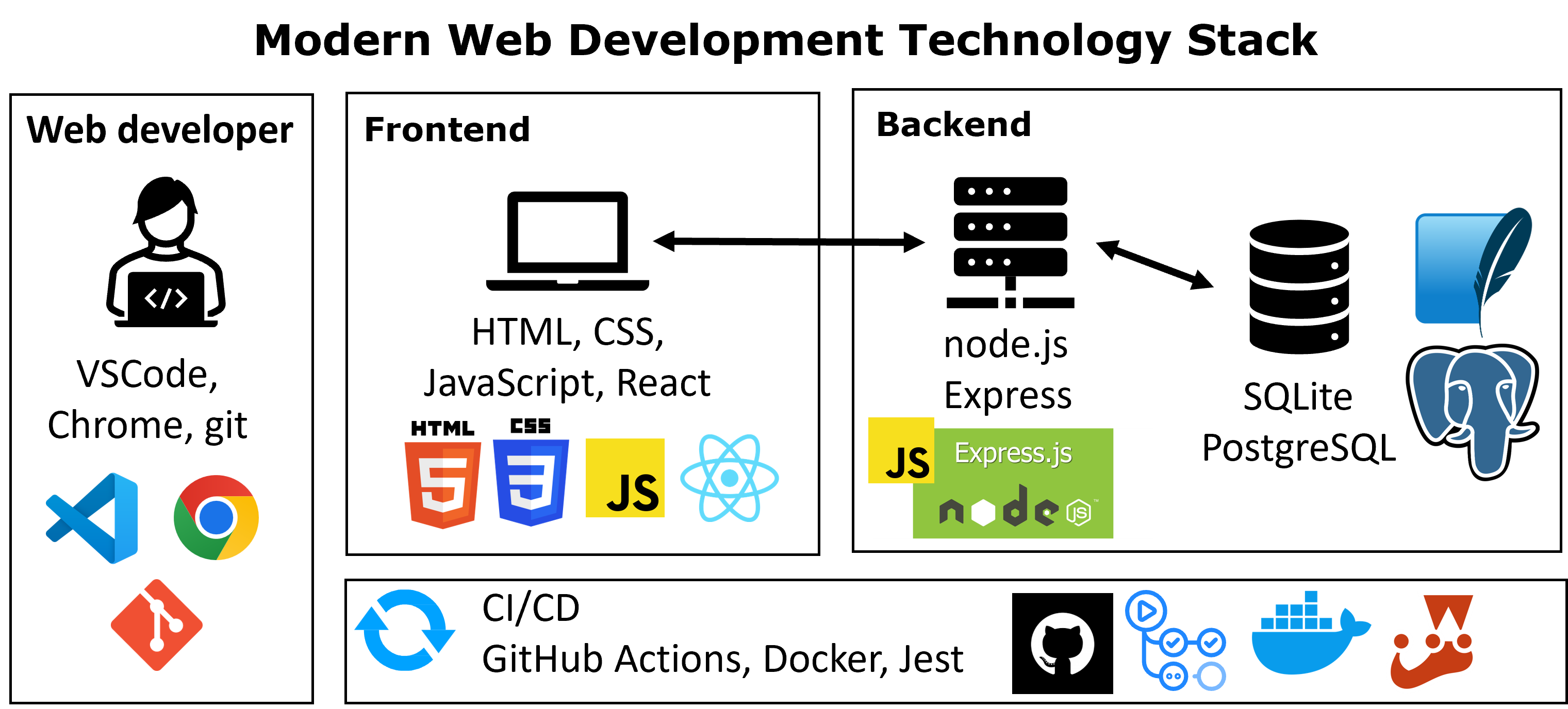

Course structure

Agenda

- JavaScript

- Asynchronous programming

- Timers

- Callback

- Promises

- asynch/await

Asynchronous programming

- In JavaScript, synchronous code is executed in a blocking manner, meaning that the code is executed serially, one statement at a time.

- In JavaScript, asynchronous programming is a fundamental part of the language. It is the mechanism that allows us to perform operations in the background, without blocking the execution of the main thread.

- This is especially important in the browser, where the main thread is responsible for updating the user interface and responding to user actions.

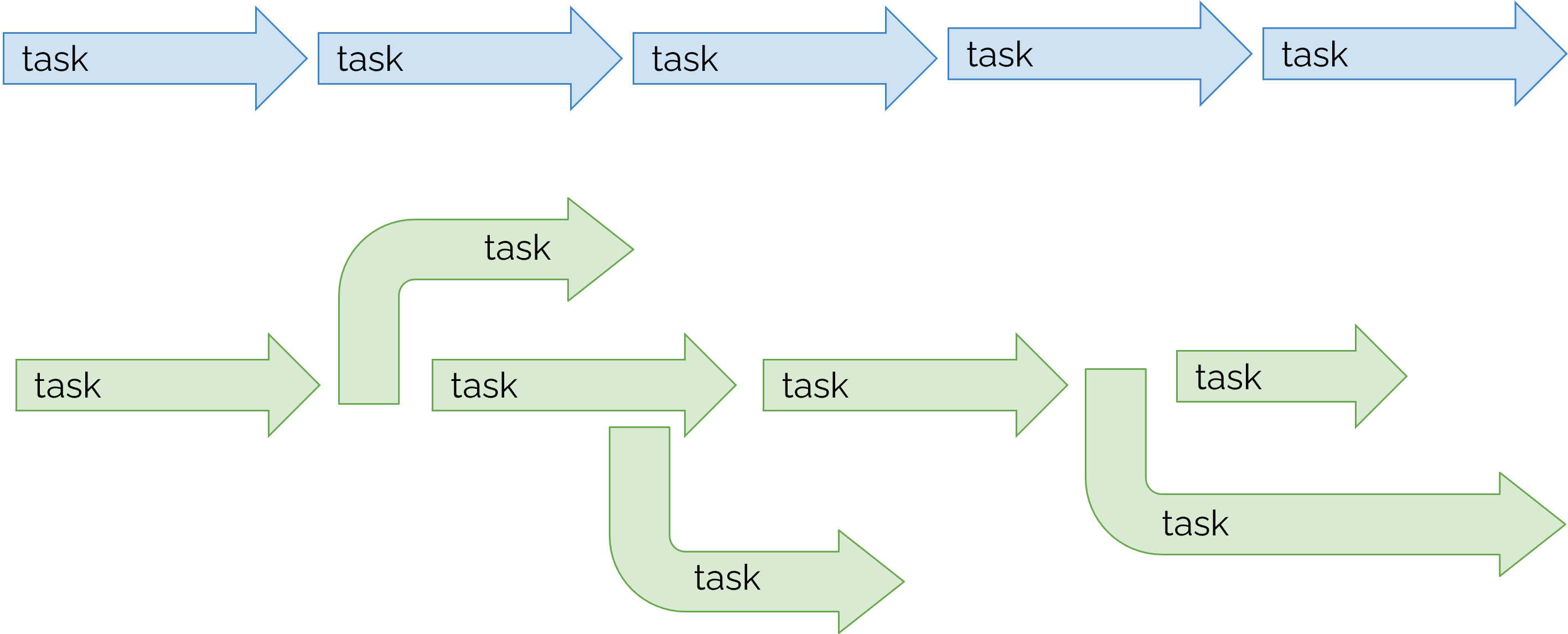

- In the figure below, the blue arrow tasks represent synchronous programming, whereas the green arrow tasks represent asynchronous programming

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous systems

Synchronous system

- Images are loaded serially, one image at a time.

![]()

Asynchronous system

- Images are loaded parallely, every image at its own time.

![]()

Why is JavaScript so different?

- Java, and other compiled languages, are often used to build systems.

- Objects are great to compose together to build complex systems.

- Systems must be reliable - a benefit of strict types, compiling, and well-defined behavior in Java.

- JavaScript is used to interact and communicate.

- It listens.

- It responds.

- It requests.

- Whereas in Java, programs often have a well-defined specification (behavior), JS has to deal with uncertainty (unusual user behavior, unavailable servers, no internet connection, etc.)

The asynchronous mindset

- To master asynchronous programming, start thinking about your code in a non-linear way.

- Instead of writing linear code, structure it around events and outcomes.

JavaScript offers three main asynchronous tools:

- Callbacks: Functions passed and executed when events occur. Simple but can lead to “callback hell.”

- Promises: Introduced in ES6, provide a cleaner way to manage async flows with better readability and state tracking.

- Async/Await: Syntax sugar over promises, enabling more readable and maintainable code.

Event listeners are asynchronous

- Event listeners can be specified as callback function, which is asynchronous programming

- Think about it, when we add the event listener, we are not executing

callbackFnor the anonymous function right away. - Those functions are executed when the click event happens.

Callback functions

- Callbacks exploit JavaScript’s capability to pass functions.

- There are two essential parts to this technique:

- A function that is passed as an argument to another function

- The passed function is executed when a certain event happens

- Let’s see an example of a callback function

- Callbacks are just a pattern where we expect that the next function to be executed is actually called as the final step (call me back when you are done - callback)

- Note that the function that is passed as an argument is not executed immediately.

Callback functions with parameters

- It is also possible to pass a function that receives arguments.

Timers and intervals

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

setTimeout(callBack, delayMS) |

Arranges to call given function after given delayMS, returns timer id |

setInterval(callBack, delayMS) |

Arranges to call function repeatedly every delayMS ms, returns timer id |

clearTimeout(timerID) |

Stop the given timer |

clearInterval(timerID) |

Stop the given interval |

- There are two functions that are commonly used to delay the execution of a function,

setTimeoutandsetInterval. - Both function sreceive a callback as an argument and execute it after a certain amount of time

- Both

setTimeoutandsetIntervalreturn an ID representing the timer. - A unique identifier the window has access to in order to manage the page timers.

- If you have access to the id, you can tell the window to stop that particular timer by passing it to

clearTimeout/clearIntervallater

setTimeout example

HTML code

JS code

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', init);

function init() {

id("demo-btn").addEventListener("click", delayedMessage);

}

function delayedMessage() {

id("output-text").textContent = "It's gonna be legend...wait for it...";

setTimeout(sayHello, 3000);

}

function sayHello() { // called when the timer goes off

id("output-text").textContent = "dary... Legendary!";

}setInterval example

HTML code

JS code

Error first callbacks

- The most common way to handle errors in callbacks is to use the error first pattern.

- This pattern consists of passing an error as the first argument of the callback, and the result as the second argument.

- In the example below,

cbreceives two arguments, an error and a result. - In the example on the left, we pass an error, whereas in the example of the right, we pass a success result.

Callback hell

- Callbacks are not easy to read, and when there are a lot of nested callbacs, the code becomes very hard to understand.

- This is called callback hell, and it is a common problem when using callbacks.

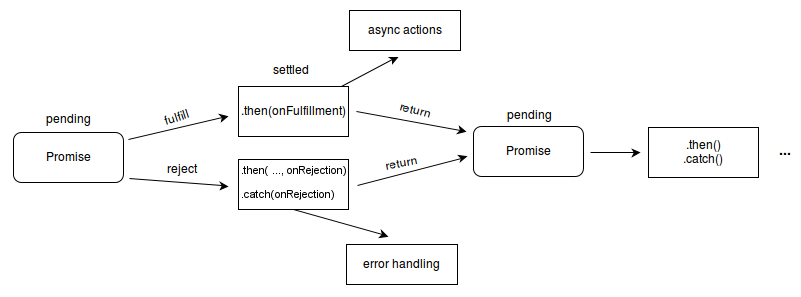

Promises

- The

Promiseobject represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation and its resulting value. - A promise has states, and it can exist in any of three states: pending, fulfilled, or rejected.

- When a promise is created, it is in the pending state. When a promise is fulfilled, it is in the fulfilled state. When a promise is rejected, it is in the rejected state.

- After a promise is fulfilled or rejected, it becomes unchangeable

- To manage fulfillment, the

thenmethod is employed, while thecatchmethod is used to address the rejection of the promise.

- To manage fulfillment, the

Example of Promises

- Let’s see how this works with a simple example using

fetchto make a request to an external application programming interface (API).

fetch('https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/gengar')

.then(response => response.json())

.then(json => console.log(json))

.catch(error => console.log(error));

Creating promises

- You can create a promise using the Promise constructor, which receives a callback function as an argument (

excutorFnin the code example). - This callback function receives two arguments, resolve and reject.

- The resolve function is used to resolve the promise, and the reject function is used to reject the promise.

excutorFNeventually determines the state of the promise- It is up to us to define this executor function

- When created, the

Promisealways initially has a state of pending

Example of creating a promise

- In this example, we have a function called

setTimeoutPromisethat receives a time as an argument. - This function returns a promise that will be resolved after the specified time. When the promise is resolved, we print one second later to the console.

function setTimeoutPromise(time) {

function executorFunction(resolve, reject) {

setTimeout(function () {

resolve();

}, time);

}

return new Promise(executorFunction);

}

console.log('Before setTimeoutPromise');

setTimeoutPromise(1000).then(function () {

console.log('one second later');

});

console.log('After setTimeoutPromise');Callback hell with promises

Promises are a great way to deal with the limitations that callbacks introduce when we need to perform multiple asynchronous operations that should be executed in a consecutive order.

Promises will handle errors more easily, so the readability of the code should be clearer and easier to maintain in long term.

readFile("docs.md") // returns a Promise

.then(convertMarkdownToHTML) // gets the content of docs.md

.then(addCssStyles) // gets the HTML from the previous step

.then(docs => saveFile(docs, "docs.html")) // saves the final version

.then(ftp.sync) // syncs to the server

.then(result => {

// do something with result

})

.catch(error => console.log(error));- Note that Each .

then(...)receives the resolved value from the previous Promise, and passes its own result to the next.then().- This means that when you pass a function reference like in the left code block, is the same as writing the contents of the right code block

async/await

- ES2017 introduced a new way to handle asynchronous code, the

asyncandawaitkeywords. - These keywords are syntactic sugar for promises

- they are not a new way to handle asynchronous code, but they make the code much easier to read and write

asyncwraps the return value in a Promise whose resolved value is the return valueawaithalts execution of the code within scope of the function it’s defined in until the Promise is resolved and then returns the resolved value of the promise- async/await are useful because it makes our code “look” synchronous again

- You don’t need callbacks, you can just have regular functions

Using async keyword (trivial example)

- Labeling a function as async wraps the function in a Promise

- Take a look in the differences between what gets printed to the console

Using await keyword (trivial example)

function newPromise(time) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(resolve, time, 'wow');

});

}

// Example 1: Using .then() to handle the resolved value

let example1 = newPromise(2000);

example1.then(result => {

console.log(result + ' that was simple (promise)');

});

// Example 2: Using await (inside an async function)

async function runExample2(time) {

let example2 = await newPromise(time);

console.log(example2 + ' that was simple (async/await');

}

runExample2(4000);- Using

awaitmeans that we are halting the execution of our code until the Promise has resolved (or rejected) - Look at the differences between the log statements

- If you use the

awaitkeyword inside of a function, the functions needs to be labeled asasync - All

asyncfunctions need to be awaited when called

Error Handling with async/await

- Utilize the try/catch block

- All code to execute in success cases goes in the try block

- Error handling code goes in the catch block

- Anything awaited belongs in a try block

Next week

Backend development and Introduction to Node.js

Acknowledgements

- Some contents of this lecture are partially adapted from:

- Harvard CS50’s Web Programming with Python and JavaScript, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- Materials from University of Washington’s CSE 154 Web Programming (used with permission).

- The Odin Project (main website code under MIT license and curriculum licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- The Fundamentals of Web Application Development (Web Edition) ©2025 Nicholas D. Freeman. All rights reserved. The content is provided for educational purposes only and is not an exhaustive treatment of the subjects.

- freeCodeCamp.org © 2025 freeCodeCamp.org. All rights reserved. The content is provided for educational purposes only and is not an exhaustive treatment of the subjects.

- Node.js for Beginners by Ulises Gascón. Some contents adapted under fair educational use for instructional purposes.

Web Programming